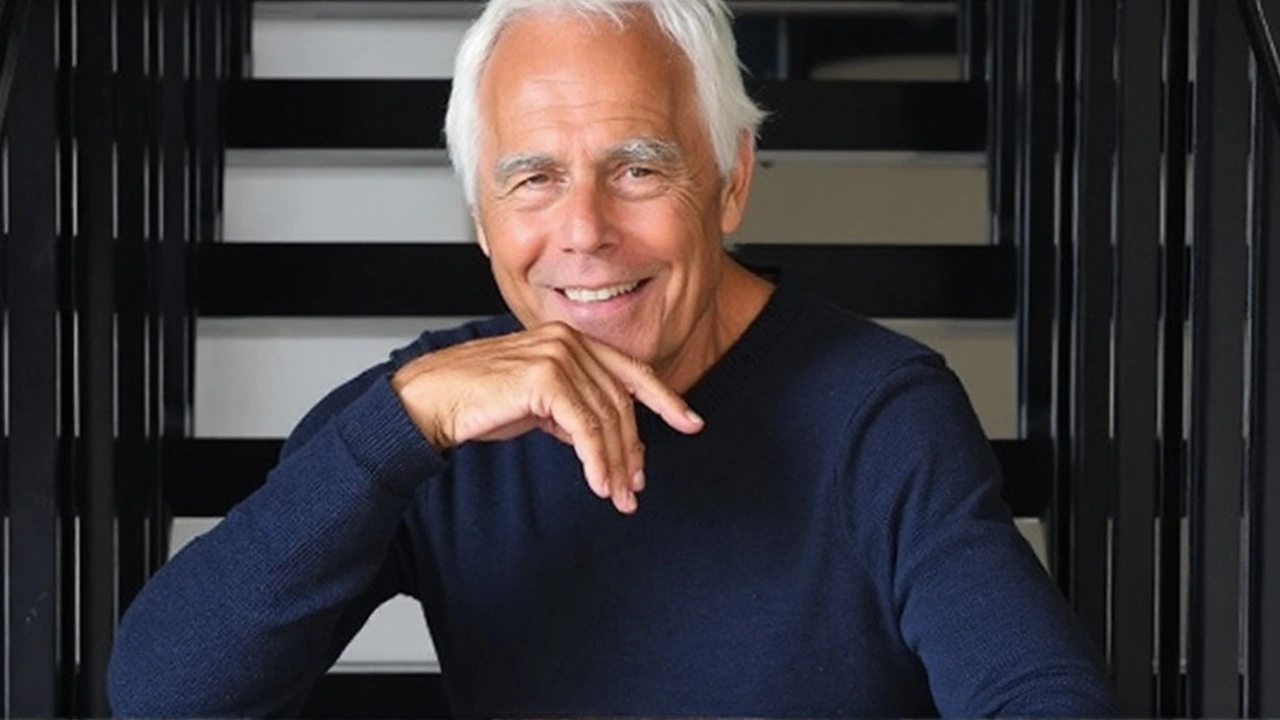

The man who made power look effortless

He took the padding out of jackets, turned black, gray and beige into a global uniform, and taught executives and actors that confidence can be quiet. Giorgio Armani, the most influential Italian fashion designer of the last half-century, died at 91, his company said on Thursday, September 4, 2025.

In a note to staff and partners, the Armani Group said he died peacefully at home, surrounded by loved ones. He had been battling an undisclosed illness that kept him away from three company shows over the summer and from the June 2025 presentations during the Spring–Summer 2026 menswear previews—his first such absence in decades. The timing is poignant: Milan was preparing to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Giorgio Armani label later this month.

Colleagues described a founder who refused to slow down. Even in his 90s, he kept a daily studio routine, checked fittings, and signed off on fabrics and lighting plans. The company called him tireless and independent, traits that defined both his runway and his business.

Armani was born on July 11, 1934. He studied medicine at the University of Milan before leaving in 1953 to serve in the military. Back in civilian life, he landed a job dressing windows at a Milan department store, then moved into design. He made his name in menswear at Nino Cerruti in the 1960s, learning tailoring at speed. In 1975, he founded his own house with Sergio Galeotti—his business and romantic partner—launching in Milan with an unlined jacket, lean trousers, and a cool urban palette. The look traveled fast.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, Armani had made Italian ready-to-wear the benchmark for modern dressing. He relaxed the suit, softening shoulders and stripping away structure. His colors—what he famously called “greige”—gave boardrooms and film sets a modern hush. Hollywood noticed. American Gigolo (1980) put his blazers and shirts on the big screen. So did television, as his fluid tailoring bled into the wardrobes of news anchors and detectives. The “power suit” could be plush and quiet, and women wore it too, thanks to his early womenswear that mirrored menswear without the stiffness.

From there, the empire grew. Giorgio Armani on the runway. Emporio Armani for a younger global audience. Armani Exchange (A|X) for street and denim. Armani Privé couture for red carpets. EA7 for sport. Then came accessories, eyewear, watches, home design, restaurants, chocolates, floral boutiques, and beauty and fragrance. The group built hotels in Milan and Dubai, and a design museum and show space—Armani/Silos and the Armani Teatro—in his home city. At the time of his death, the business he controlled had an estimated value north of $10 billion, placing him among the world’s wealthiest founders.

Unlike many rivals, Armani kept his group privately held and tightly run. He resisted IPOs and foreign buyers, preferring control over size. Years ago he set up a foundation structure to protect the brand’s independence and fund cultural and social projects, a move widely read as his plan to steer succession and keep the company Italian in spirit and base.

Inside the studio, Armani trusted a small circle. For years, Leo Dell’Orco has overseen menswear, while his niece Silvana Armani has led womenswear. Roberta Armani built the brand’s deep ties with film. In recent months, he had been signaling continuity through this team, and the company’s statement pointed to that long-prepared leadership bench. Industry watchers expect a collective model—anchored by those lieutenants and the foundation arrangements—to keep the codes intact.

Armani’s design language barely budged because it didn’t need to. Neat shoulders, soft fabrics, longer lines. Neutral tones that suit almost any light. He rejected loud logos long before it became fashionable to do so again. His aesthetic carried into Armani Casa interiors, restaurant dining rooms, and even hotel lobbies: calm surfaces, measured light, nothing shouting for attention. He called it “style” rather than fashion—and he stuck to it.

He also had a public streak of practicality, stepping into real-world crises when he felt it mattered. During the early months of the pandemic, Armani funded hospitals and redirected his factories to protective gowns for health workers in Italy. He later emphasized sustainability and ethics in materials, including commitments to move away from animal fur, and invested in supply-chain traceability to preserve Italian manufacturing skills.

His reach wasn’t only on runways. In offices from New York to Tokyo, managers wore his soft suits. On carpets from the Oscars to Venice, actors defaulted to his tuxedos and column gowns. His clothes were a kind of universal passport: familiar enough for a board meeting, polished enough for a premiere. That balance—ease plus authority—became his signature and a global export for Milan.

The business he leaves behind spans many price points and channels. Beauty sits alongside couture; outlet stores live next to flagship “cathedrals.” Licenses in eyewear and watches built volume, while in-house categories protected quality. The tight control meant slower expansion than some peers, but far fewer identity swings. Customers knew what they were getting: refined lines, expensive-feeling fabrics, and a promise that the piece would still look right in 10 years.

Armani’s personal story is woven into the company’s milestones. His partner Sergio Galeotti, who helped propel the brand in its early burst of growth, died in 1985. Armani responded by consolidating control and doubling down on the core look rather than chasing trends. He opened the Via Borgonuovo headquarters in Milan, then pioneered the modern luxury “world” store with dining, home, and fashion under one roof. Each move strengthened the house while keeping it centered on Milanese restraint.

The next question is continuity. The brand’s codes are among the clearest in fashion, which makes them easier to protect but also easy to ossify if mishandled. Expect the studio to keep refining the suit, separating day from evening with clean cuts and subtle sparkle, and guarding the muted palette that made Armani a daily uniform for so many. The 50th anniversary shows, now carrying the weight of a tribute, will likely underline that DNA rather than reinvent it.

The company said a public farewell will take place at the Armani Teatro in Milan from Saturday, September 6, to Sunday, September 7, giving fans, employees, and the city a chance to pay respects. A private funeral will follow.

How Armani reshaped fashion—and what remains

Armani’s legacy is not just garments but a way of seeing clothes as tools. He trusted the body and let fabric do the work. He proved that minimalism can sell at scale if it flatters and functions. He made luxury feel useful—rare in a business that often chases spectacle.

- 1975: Launches Giorgio Armani with Sergio Galeotti in Milan, starting with soft tailoring that breaks with stiff, padded suits.

- Late 1970s–1980s: Brings Italian ready-to-wear to the world; Hollywood and television amplify his relaxed power look.

- 1981 onward: Builds a brand family—Emporio Armani, Armani Exchange, Armani Privé—and expands into accessories and lifestyle.

- 2000s–2010s: Opens hotels and cultural spaces, blending fashion with hospitality and design while keeping control of the group.

- 2020s: Reinforces independence and succession planning; continues designing deep into his 90s.

His influence shows up every time a suit moves like a cardigan, every time a red-carpet dress glides instead of shouts, every time a brand treats silence as a luxury. That approach is now part of the global wardrobe. The team he trained inherits not just a company but a clear blueprint: reduce, refine, repeat.

Shaun Collins

Armani bland suits finally got the attention they never deserved.